A film of faces. A tapestry of close ups. A story told with minimalism and grace. Joan of Arc’s trial and execution is one of history’s worst instances of the power of government over the individual. It’s an important tale to tell, filmed by Dreyer with quiet compassion and intense intimacy.

Intimate intensity may seem like an oxymoron but, as this film proves, this is not always the case. The simplistic approach, relying primarily on close ups and faces to tell the story, allows for intimacy. A closeness to the action. Like we’re all there. Yet it’s this same intimacy that leads to intensity. We feel the metaphorical spotlight. We feel the fear, fervour, fire. We feel the trial.

Beyond the stylistic attributes, there’s a timeless theme at the root. An important one to note, too. Oppression at the hands of a malevolent state. The persecution of the individual. The person against the mob. To say that Joan was killed by religion would be erroneous. She was killed by the forces of government. It is now regarded as a sham of a trial, performed for dubious secular reasons. They used religion and the concept of canon law to get rid of someone who posed a threat to their goals, despite the fact that according to such laws Joan was innocent. Nonetheless, biblical law was cited to justify her execution. From this, one can conclude that it is Joan's version of faith, not that of the prosecution, which is the purer representation of Christian principles. We don't need to be religious spectators to see that.

Again, this film is one of the best arguments against state interference in both the lives of individuals and in religious matters. It's timeless because even today, all across the world, liberty and the natural right of freedom are being infringed upon and vehemently defended with equal measure. Indeed, Joan was fighting tyranny when she was captured. This film makes an impassioned plea to its viewers, through the face of Joan, against such malicious forces of oppression.

Joan's courage, devotion and strength is fully realised by Falconetti's shattering performance. It is often cited as perhaps the best female performance on film. Beyond that, some would even say the greatest performance full stop. Well, it's hard to measure such subjective feats but it is certainly up there as one of the all time bests. Praise should also be extended to the rest of the cast. They too offered devotion to the film, fully complying with Dreyer's strict policies and the hard work required to obtain this film's ambitious and striking realism.

It's crucial to observe, however, that the minimalist approach doesn't necessarily mean that the film is lacking in little flourishes or is restricted in style. There are plenty of shots that are complex and inventive in technique. Particularly some glorious tracking movements filmed some 30 years before Kubrick and 40 years before Scorsese. One reason this film ages so well is that it isn't really dated by anything except its lack of sound and colour. If this were coloured and dubbed (not that such a thing should ever happen), it'd be practically indistinguishable from modern day films. Nonetheless, the silence and beautiful black and white cinematography give this film an ethereal boost. Interestingly, there's also the option to watch this film completely silent, without even a score. Some think of this as a benefit, others prefer to watch it with music. Regardless of your choice, The Passion of Joan of Arc will no doubt touch you.

This film, nearing it's 90th birthday, is a timeless classic. A film in which ugliness and beauty, bad and good, death and life all come together to play. They fit alongside each other on the puzzle known as the human experience, presented here in all its glory and shame.

The Passion of Joan of Arc review

Posted : 11 years, 3 months ago on 17 November 2014 04:32

(A review of The Passion of Joan of Arc)

Posted : 11 years, 3 months ago on 17 November 2014 04:32

(A review of The Passion of Joan of Arc) 0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

A multi-layered masterpiece

Posted : 13 years, 11 months ago on 10 March 2012 09:24

(A review of The Raven)

Posted : 13 years, 11 months ago on 10 March 2012 09:24

(A review of The Raven)The Raven is the peak of what is often regarded as The Stranglers best period of music, beginning in 1977 with their groundbreaking album Rattus Norvegicus. In these three productive years, four studio albums were released. Rattus Norvegicus and No More Heroes, both released in 1977, Black and White in 1978 and The Raven in 1979. The pick of the bunch, The Raven is a multi-layered album, full of diverse and unique tracks. What’s sad about The Stranglers is that, despite their commercial success at the height of the Punk movement and the fact that they lasted longer than any of the other leading groups, nowadays, they are almost forgotten in the shadow of The Clash and The Sex Pistols. The latter two are, obviously, of vital significance. Both were responsible for some legendary music, as well as encompassing the attitude of the times. However, The Stranglers were also vessels for a changing outlook, with iconic single No More Heroes perfectly conveying that. So why are they so overlooked today? Not only were they able to contribute to the raw, violent sound of Punk rock, they managed to weave in their own style, employing a prominent but not overbearing use of the Keyboard. This album is the perfect example to accentuate the tragedy of their under-rated status.

By 1979, they were beginning to build upon their already established talent of rhythm and theme transcending lyrics. Punk sentiment mixed with a versatile level of surrealism, seen in the roots of their career and fully explored here. The Raven is their magnum opus, a commercial and critical success, lately glazed over by rock fans and critics alike.

They kick off the album with short instrumental Longships, one of two songs that explores the Nordic concept, which they abandon after the eponymous second song. The two songs are well mixed, combining thick basslines with a softer keyboard texture, subtle drumming and well placed guitar twangs. Two songs that highlight the best feature of The Stranglers, an ability to intertwine their instruments on an equal level, giving precedence to no particular band member. Whilst most Punk music at the time was driven by ragged guitar and a sporadic use of drums and bass, The Stranglers took a more Progressive Rock approach. Musically, they are on the same level as Pink Floyd, themselves masters of texturing. Although unlike them, The Stranglers weren’t hated by the Punk community because deep down, they weren’t afraid to play up their Punk credentials. In attitude at least, they were still on the same wavelength.

The third track of the record, amongst the best of the album, is the one song in which a particular instrument is given priority. The driving basslines of the brilliantly titled Dead Loss Angeles, a name mixing the idiom ‘dead loss’ with the famous Californian city, were achieved by having both bassist JJ Burnel and guitarist Hugh Cornwell playing the instrument. Meanwhile, the name of the song is a perfect summary of the satirical lyrics, which include such attacks as ‘android Americans, live in the ruins there’. Hugh Cornwell sings lead vocals, suiting the pace of the song. The heavy track is followed by the equally brilliant and more intricate Ice, a masterpiece of composition, with an incredible opening and closing instrumentation to boot. Meanwhile. It’s one of the best tracks that showcases the incredible talent of drummer Jet Black and keyboardist Dave Greenfield.

However, it is the 8th track, the sombre Don’t Bring Harry, that truly shines. A melodic anti-drugs song straight from the heart of the members, particularly lead vocalist on the song, JJ Burnel. His baritone voice works wonders with the poignant lyrics, which due to their broadness, isn’t restricted to only those who share in their drug use experiences. It can be attributed to both depression and paranoia, depending on how you look at the lyrics. Either way, with lines such as ‘once there was laughter, now there’s compromise’, it is an incredibly deep song. Released as a single, it was unsuccessful, perhaps due to its dark overtones. Comparatively, leading single Duchess proved to be more of a hit, reaching number 14 in the charts. Yet this outcome is understandable, based on its commercial accessibility as a song and the controversy sparked by the music video. As the adage goes, ‘all publicity is good publicity’.

Other highlights from the album include the vividly surreal Meninblack, featuring distinctive guitar parts by Cornwell and one of the best uses of experimental vocal modification, album closure Genetix, sung by keyboardist Greenfield and the humorous pasquinade Nuclear Device.

This is the best album that no one pays attention to. With all the fame garnered by Peaches and Golden Brown, few people ever endeavour to explore the rest of their discography. If they did, they would learn that these two singles (from 1977 and 1981 respectively), simply signal the tip of the iceberg. For an album that reached number four in the charts and one that is surrounded by the belief that it was cheated off the number one spot by a chart error, it is amazing how it has since come to be covered with dust, left aside in favour of other seventies albums from the era. Such a lack of appreciation can be seen in books like 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (2011, Quintessence Editions), in which just one album makes the grade (Rattus Norvegicus) and 1001 Songs You Must Hear Before You Die (2010, Quintessence), in which Peaches remains the only represented song, further demonstrating the effects of the Iceberg issue. For casual listeners there is an excuse but for professional music critics? As good as these books are, giving Coldplay more attention (two albums, two songs), isn’t a fair assessment of musical talent. Furthermore, Rolling Stone Magazine, who I by no means endorse, leave Hugh Cornwell off their list of 100 Greatest Guitarists. Not unlike Pete Townshend, he isn't known for his solos, rather his overall contribution to the texture of the music. Yet unlike Pete Townshend, he is left off the list completely.

Digressions aside, The Raven is an example of admirable craftsmanship, a high point in a shamefully ignored career, by one of the most important, unique and daring of all artists from the late seventies. The album is well produced, an example of exceptional subtlety, with each member bringing a significant amount of talent to the recordings. It’s this album that also saw the seeds sown for their next release, the concept album The Gospel According to the Meninblack, their 1981 foray into the themes of outer space.

Highlight tracks:

Don't Bring Harry

Ice

Dead Loss Angeles

By 1979, they were beginning to build upon their already established talent of rhythm and theme transcending lyrics. Punk sentiment mixed with a versatile level of surrealism, seen in the roots of their career and fully explored here. The Raven is their magnum opus, a commercial and critical success, lately glazed over by rock fans and critics alike.

They kick off the album with short instrumental Longships, one of two songs that explores the Nordic concept, which they abandon after the eponymous second song. The two songs are well mixed, combining thick basslines with a softer keyboard texture, subtle drumming and well placed guitar twangs. Two songs that highlight the best feature of The Stranglers, an ability to intertwine their instruments on an equal level, giving precedence to no particular band member. Whilst most Punk music at the time was driven by ragged guitar and a sporadic use of drums and bass, The Stranglers took a more Progressive Rock approach. Musically, they are on the same level as Pink Floyd, themselves masters of texturing. Although unlike them, The Stranglers weren’t hated by the Punk community because deep down, they weren’t afraid to play up their Punk credentials. In attitude at least, they were still on the same wavelength.

The third track of the record, amongst the best of the album, is the one song in which a particular instrument is given priority. The driving basslines of the brilliantly titled Dead Loss Angeles, a name mixing the idiom ‘dead loss’ with the famous Californian city, were achieved by having both bassist JJ Burnel and guitarist Hugh Cornwell playing the instrument. Meanwhile, the name of the song is a perfect summary of the satirical lyrics, which include such attacks as ‘android Americans, live in the ruins there’. Hugh Cornwell sings lead vocals, suiting the pace of the song. The heavy track is followed by the equally brilliant and more intricate Ice, a masterpiece of composition, with an incredible opening and closing instrumentation to boot. Meanwhile. It’s one of the best tracks that showcases the incredible talent of drummer Jet Black and keyboardist Dave Greenfield.

However, it is the 8th track, the sombre Don’t Bring Harry, that truly shines. A melodic anti-drugs song straight from the heart of the members, particularly lead vocalist on the song, JJ Burnel. His baritone voice works wonders with the poignant lyrics, which due to their broadness, isn’t restricted to only those who share in their drug use experiences. It can be attributed to both depression and paranoia, depending on how you look at the lyrics. Either way, with lines such as ‘once there was laughter, now there’s compromise’, it is an incredibly deep song. Released as a single, it was unsuccessful, perhaps due to its dark overtones. Comparatively, leading single Duchess proved to be more of a hit, reaching number 14 in the charts. Yet this outcome is understandable, based on its commercial accessibility as a song and the controversy sparked by the music video. As the adage goes, ‘all publicity is good publicity’.

Other highlights from the album include the vividly surreal Meninblack, featuring distinctive guitar parts by Cornwell and one of the best uses of experimental vocal modification, album closure Genetix, sung by keyboardist Greenfield and the humorous pasquinade Nuclear Device.

This is the best album that no one pays attention to. With all the fame garnered by Peaches and Golden Brown, few people ever endeavour to explore the rest of their discography. If they did, they would learn that these two singles (from 1977 and 1981 respectively), simply signal the tip of the iceberg. For an album that reached number four in the charts and one that is surrounded by the belief that it was cheated off the number one spot by a chart error, it is amazing how it has since come to be covered with dust, left aside in favour of other seventies albums from the era. Such a lack of appreciation can be seen in books like 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (2011, Quintessence Editions), in which just one album makes the grade (Rattus Norvegicus) and 1001 Songs You Must Hear Before You Die (2010, Quintessence), in which Peaches remains the only represented song, further demonstrating the effects of the Iceberg issue. For casual listeners there is an excuse but for professional music critics? As good as these books are, giving Coldplay more attention (two albums, two songs), isn’t a fair assessment of musical talent. Furthermore, Rolling Stone Magazine, who I by no means endorse, leave Hugh Cornwell off their list of 100 Greatest Guitarists. Not unlike Pete Townshend, he isn't known for his solos, rather his overall contribution to the texture of the music. Yet unlike Pete Townshend, he is left off the list completely.

Digressions aside, The Raven is an example of admirable craftsmanship, a high point in a shamefully ignored career, by one of the most important, unique and daring of all artists from the late seventies. The album is well produced, an example of exceptional subtlety, with each member bringing a significant amount of talent to the recordings. It’s this album that also saw the seeds sown for their next release, the concept album The Gospel According to the Meninblack, their 1981 foray into the themes of outer space.

Highlight tracks:

Don't Bring Harry

Ice

Dead Loss Angeles

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

A towering magnum opus

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 6 March 2012 07:07

(A review of 898r43)

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 6 March 2012 07:07

(A review of 898r43)Released in 1968, this self-titled album, commonly referred to as The White Album, is a standout amongst their already effervescent discography. Whilst it lacks the easy listening of A Hard Day’s Night (1964), the consistency of Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) and the fluidity of Abbey Road (1969), The White Album is arguably the band’s most inventive record.

A diverse album of influential classics, the track list includes such identifiable numbers as Helter Skelter, Revolution 1, Happiness Is a Warm Gun, While My Guitar Gently Weeps and Dear Prudence. The latter has been covered by many other artists, including a brilliant version by new-wave punk group Siouxsie and the Banshees, one of the strongest Beatles covers to date. It is an accessible album for everyone. It has songs reminiscent of their earlier work (Ob-La-Di Ob-La Da, Don't Pass Me By, Honey Pie), songs that were in keeping with their post 1966 sound (The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill, Piggies, Rocky Raccoon) and some ingenious compositions that were well ahead of their time (Wild Honey Pie, Helter Skelter, Sexy Sadie). It is effectively their decade spanning sound condensed into one double album, which is possibly the greatest idea they could have had.

The album is a work of recording genius, with some of the tightest, best produced and well executed songs of their career. The sweeping arrangements of Savoy Truffle, Good Night and Honey Pie and the ambitious complexity of Helter Skelter, Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Monkey and The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill contrast excellently with the gorgeous simplicity of Blackbird, Julia and Mother Nature’s Son. Whilst the album as a whole is comparatively minimal to the big band sound of Sgt. Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour and Revolver, The White Album isn’t without its magnitude, as highlighted with some of the previously mentioned songs that use such arrangements. However, it definitely has a nice, simpler sound overall, signified from the offset with its stark white cover. Their more relaxed, acoustic tone can be traced back to their stay in India, where they wrote many of the songs included. Incidentally, the calming effect juxtaposes with the tumultuous period in which these tracks were first conceived.

Just over a year away from splitting up, cracks were beginning to show. Ringo Starr even left during the early stages of the recording, with Paul McCartney filling in for him on the first two tracks. Soon after, George Harrison briefly left. However, it is possible that this conflict helped drive the band’s creativity, particularly evident in the loud and raucous Helter Skelter, often attributed as a precursor of Heavy Metal. After 15+ takes, the band had created a song that is one of the most essential and inspirational tracks ever recorded. The session was so intense that it even gave Ringo blisters, a fact he screams iconically at the end of the song. If you want to whack out a track that supports your ‘Ringo wasn’t a bad drummer’ argument, this is your best bet, along with A Day in the Life, The End and Strawberry Fields Forever, all from three separate albums respectively, a clear sign of his consistent and under-rated talent. Helter Skelter also serves as a rare track in which only Starr plays his regular instrument; McCartney takes over Harrison’s usual role as lead guitarist, who in turn plays the rhythm parts usually undertaken by John, who here plays the bass that is normally played by McCartney.

The White Album is an example of a timeless masterpiece, with a sound more modern than that of A Hard Day’s Night, Beatles for Sale and even Sgt. Pepper, which was from the preceding year. Along with the incredibly progressive Abbey Road, The White Album is their most enduring work. A cornerstone of the music industry, its influence can be detected in songs from the crop of modern bands. The single Karma Police by Radiohead, which can be found on their 1997 masterpiece OK Computer, bears notable similarities to Sexy Sadie, one of The White Album’s best tracks. Meanwhile, the influence of Helter Skelter is still overt in today’s music, in recordings by bands such as Queens of the Stone Age and Marilyn Manson, the latter of which even recorded a cover version.

Whilst it is often Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that is billed as their best work, it is The White Album that truly leaves its mark. With solid contributions from all four members, including one of the two sole creations of Ringo Starr, it is an album where their collective talents are extremely well exhibited. It’s also an album that splits its audience. Its crowd-dividing nature can be epitomised by one song. Revolution 9.

Highlight tracks:

Helter Skelter

Piggies

Revolution 9

The Continuing Story of Buffalo Bill

Sexy Sadie

Rocky Raccoon

A diverse album of influential classics, the track list includes such identifiable numbers as Helter Skelter, Revolution 1, Happiness Is a Warm Gun, While My Guitar Gently Weeps and Dear Prudence. The latter has been covered by many other artists, including a brilliant version by new-wave punk group Siouxsie and the Banshees, one of the strongest Beatles covers to date. It is an accessible album for everyone. It has songs reminiscent of their earlier work (Ob-La-Di Ob-La Da, Don't Pass Me By, Honey Pie), songs that were in keeping with their post 1966 sound (The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill, Piggies, Rocky Raccoon) and some ingenious compositions that were well ahead of their time (Wild Honey Pie, Helter Skelter, Sexy Sadie). It is effectively their decade spanning sound condensed into one double album, which is possibly the greatest idea they could have had.

The album is a work of recording genius, with some of the tightest, best produced and well executed songs of their career. The sweeping arrangements of Savoy Truffle, Good Night and Honey Pie and the ambitious complexity of Helter Skelter, Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Monkey and The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill contrast excellently with the gorgeous simplicity of Blackbird, Julia and Mother Nature’s Son. Whilst the album as a whole is comparatively minimal to the big band sound of Sgt. Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour and Revolver, The White Album isn’t without its magnitude, as highlighted with some of the previously mentioned songs that use such arrangements. However, it definitely has a nice, simpler sound overall, signified from the offset with its stark white cover. Their more relaxed, acoustic tone can be traced back to their stay in India, where they wrote many of the songs included. Incidentally, the calming effect juxtaposes with the tumultuous period in which these tracks were first conceived.

Just over a year away from splitting up, cracks were beginning to show. Ringo Starr even left during the early stages of the recording, with Paul McCartney filling in for him on the first two tracks. Soon after, George Harrison briefly left. However, it is possible that this conflict helped drive the band’s creativity, particularly evident in the loud and raucous Helter Skelter, often attributed as a precursor of Heavy Metal. After 15+ takes, the band had created a song that is one of the most essential and inspirational tracks ever recorded. The session was so intense that it even gave Ringo blisters, a fact he screams iconically at the end of the song. If you want to whack out a track that supports your ‘Ringo wasn’t a bad drummer’ argument, this is your best bet, along with A Day in the Life, The End and Strawberry Fields Forever, all from three separate albums respectively, a clear sign of his consistent and under-rated talent. Helter Skelter also serves as a rare track in which only Starr plays his regular instrument; McCartney takes over Harrison’s usual role as lead guitarist, who in turn plays the rhythm parts usually undertaken by John, who here plays the bass that is normally played by McCartney.

The White Album is an example of a timeless masterpiece, with a sound more modern than that of A Hard Day’s Night, Beatles for Sale and even Sgt. Pepper, which was from the preceding year. Along with the incredibly progressive Abbey Road, The White Album is their most enduring work. A cornerstone of the music industry, its influence can be detected in songs from the crop of modern bands. The single Karma Police by Radiohead, which can be found on their 1997 masterpiece OK Computer, bears notable similarities to Sexy Sadie, one of The White Album’s best tracks. Meanwhile, the influence of Helter Skelter is still overt in today’s music, in recordings by bands such as Queens of the Stone Age and Marilyn Manson, the latter of which even recorded a cover version.

Whilst it is often Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that is billed as their best work, it is The White Album that truly leaves its mark. With solid contributions from all four members, including one of the two sole creations of Ringo Starr, it is an album where their collective talents are extremely well exhibited. It’s also an album that splits its audience. Its crowd-dividing nature can be epitomised by one song. Revolution 9.

Highlight tracks:

Helter Skelter

Piggies

Revolution 9

The Continuing Story of Buffalo Bill

Sexy Sadie

Rocky Raccoon

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

A high peak of television.

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 5 March 2012 05:37

(A review of Twin Peaks)

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 5 March 2012 05:37

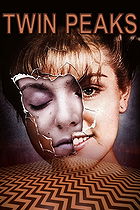

(A review of Twin Peaks)For many, Twin Peaks was the definitive television show of the 90s, despite its relatively short run. With 29 episodes in all (30 counting the feature length pilot) spread over 2 years, it managed to cover a wide variety of characters, played by a huge ensemble of talented and under-rated actors, all little pawns in a complex plotline. I thought I would throw in a little chess reference, considering the show’s final dozen episodes draw upon it as one of its primary motifs. The iconic use of the game has become one of the things most associated with the series, perhaps second only to the often referenced and infinitely creepy Red Room scenes.

Twin Peaks is both parts surreal mystery and soap-opera slush, using the latter as an ironic and almost self-parodying juxtaposition to the genuinely frightening aspects of the show. Similar in ways to the melodrama of David Lynch’s preceding film masterpiece Blue Velvet (1986), the fluffy scenes of romance and friendship are not bad traits, rather they are charming and effective methods in which to convey the homely-little-community atmosphere. Created by surrealist legend David Lynch and his friend Mark Frost, the two came up with a multi-faceted tale of horror, suspense and intrigue, full of too-many-to-count twists and turns, spread across a vast canvas of brilliant locations, populated by exceptionally interesting characters. Lynch and Frost, directors and writers of the standout episodes, thrust the eponymous small town into a surreal blender.

Twin Peaks is one of the scariest of all watchable media, up there with the classic film The Haunting (1963) and several particularly gruesome episodes of Dexter (2006-). In one early episode, I was given such a fright that I was reduced to watching the rest of the series with the lights on, save for the final few episodes, which work incredibly well in a dark room. Few things get under your skin as much as Twin Peaks, with such scary scenes handled with perfectly precise timing. For someone who has been watching horror films since I was a child and can usually brush off such things as Paranormal Activity, I was still utterly shocked by the terrifying nature of this series. Let it be said that it is Twin Peaks that pops into my head when I’m walking alone in the dark, not any recent attempts at horror. Whilst not all episodes are upfront fear mongers, the ones that are do it well. For those familiar with Lynch’s 1977 surrealist masterpiece Eraserhead, you will know all too well how competent he is at composing strange and unnerving set pieces.

You’d think that a series with such a huge ensemble of would lose its way in such a limited amount of episodes, yet several story-lines are explored successfully in such a small time frame – and not just for one set of characters. Likewise, each story arch is a captivating one, no matter how minor, major or ultimately unimportant some of the characters are. In a sense, it is similar to Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia (1999), a film of many characters, all of which have extremely gripping stories. As a microcosm of small-town America, Twin Peaks is admirable in its diverse amount of roles and strong attention to detail.

Heading the cast is Kyle MacLachlan, known previously as the likeable protagonist in the aforementioned Blue Velvet, here playing a more adept character. Unlike the naivety of Jeffrey, the quirky character of FBI Agent Dale Cooper is a strong-minded individual. Paired with the humorously named Harry S. Truman (played with rugged sensibility by Michael Ontkean), the two lawmen try to solve the mystery of Laura Palmer’s murder, an already shocking affair, which soon escalates into much more than a by-the-numbers case. Surrounding these two personas are a host of brilliant characters, including the comic relief of Deputy Andy Brennan and his amusingly difficult yet sweetly endearing relationship with receptionist Lucy Moran. Other outstanding characters are that of local businessman Benjamin Horn, played with a commanding presence by Richard Beymer (who played Tony in the film version of West Side Story – when I found out, I shat bricks, you wouldn’t have guessed they were the same person) and his wily daughter Audrey (who would later star as Curly’s wife in the 1992 adaption of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men). Alongside them is Richard Beymer’s West Side Story co star Russ Tamblyn as an eccentric psychologist, Piper Laurie (of Carrie fame) as conniving Catherine Martell, Jack Nance as her husband, looking unrecognisable 15 years after his lead role in Eraserhead and Ray Wise’s as Leland Palmer. The latter would go on to star in under-rated horror film Jeepers Creepers 2 (2003) and the television series Reaper, which gained moderate success. A rich and well chosen cast truly makes this series stronger, including the fantastically elaborate performance later in the series by Kenneth Welsh.

What makes Twin Peaks such a fascinating series, though, is the central enigma. The obscurely named Black Lodge. Every good series need an enigma. Lost had the island, Death Note had the notebook, Flash Forward, cut down in its prime, had the mass blackout, all gripping concepts with the ability to take the viewer in any direction. With The Black Lodge, even the title is intriguing.

As film-critic and chat show host Jonathan Ross once put it, Twin Peaks is ‘the scariest, weirdest and funniest TV series of all time’, a completely accurate statement. Twin Peaks is a one of a kind drama, a unique and unsurpassable landmark that helped establish television as an artistic rival of cinema. With all of its flamboyant and ambitious scenes, juxtaposing with remarkably restrained subtlety, Twin Peaks is a lurid, luscious and laudable cult classic.

Twin Peaks is both parts surreal mystery and soap-opera slush, using the latter as an ironic and almost self-parodying juxtaposition to the genuinely frightening aspects of the show. Similar in ways to the melodrama of David Lynch’s preceding film masterpiece Blue Velvet (1986), the fluffy scenes of romance and friendship are not bad traits, rather they are charming and effective methods in which to convey the homely-little-community atmosphere. Created by surrealist legend David Lynch and his friend Mark Frost, the two came up with a multi-faceted tale of horror, suspense and intrigue, full of too-many-to-count twists and turns, spread across a vast canvas of brilliant locations, populated by exceptionally interesting characters. Lynch and Frost, directors and writers of the standout episodes, thrust the eponymous small town into a surreal blender.

Twin Peaks is one of the scariest of all watchable media, up there with the classic film The Haunting (1963) and several particularly gruesome episodes of Dexter (2006-). In one early episode, I was given such a fright that I was reduced to watching the rest of the series with the lights on, save for the final few episodes, which work incredibly well in a dark room. Few things get under your skin as much as Twin Peaks, with such scary scenes handled with perfectly precise timing. For someone who has been watching horror films since I was a child and can usually brush off such things as Paranormal Activity, I was still utterly shocked by the terrifying nature of this series. Let it be said that it is Twin Peaks that pops into my head when I’m walking alone in the dark, not any recent attempts at horror. Whilst not all episodes are upfront fear mongers, the ones that are do it well. For those familiar with Lynch’s 1977 surrealist masterpiece Eraserhead, you will know all too well how competent he is at composing strange and unnerving set pieces.

You’d think that a series with such a huge ensemble of would lose its way in such a limited amount of episodes, yet several story-lines are explored successfully in such a small time frame – and not just for one set of characters. Likewise, each story arch is a captivating one, no matter how minor, major or ultimately unimportant some of the characters are. In a sense, it is similar to Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia (1999), a film of many characters, all of which have extremely gripping stories. As a microcosm of small-town America, Twin Peaks is admirable in its diverse amount of roles and strong attention to detail.

Heading the cast is Kyle MacLachlan, known previously as the likeable protagonist in the aforementioned Blue Velvet, here playing a more adept character. Unlike the naivety of Jeffrey, the quirky character of FBI Agent Dale Cooper is a strong-minded individual. Paired with the humorously named Harry S. Truman (played with rugged sensibility by Michael Ontkean), the two lawmen try to solve the mystery of Laura Palmer’s murder, an already shocking affair, which soon escalates into much more than a by-the-numbers case. Surrounding these two personas are a host of brilliant characters, including the comic relief of Deputy Andy Brennan and his amusingly difficult yet sweetly endearing relationship with receptionist Lucy Moran. Other outstanding characters are that of local businessman Benjamin Horn, played with a commanding presence by Richard Beymer (who played Tony in the film version of West Side Story – when I found out, I shat bricks, you wouldn’t have guessed they were the same person) and his wily daughter Audrey (who would later star as Curly’s wife in the 1992 adaption of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men). Alongside them is Richard Beymer’s West Side Story co star Russ Tamblyn as an eccentric psychologist, Piper Laurie (of Carrie fame) as conniving Catherine Martell, Jack Nance as her husband, looking unrecognisable 15 years after his lead role in Eraserhead and Ray Wise’s as Leland Palmer. The latter would go on to star in under-rated horror film Jeepers Creepers 2 (2003) and the television series Reaper, which gained moderate success. A rich and well chosen cast truly makes this series stronger, including the fantastically elaborate performance later in the series by Kenneth Welsh.

What makes Twin Peaks such a fascinating series, though, is the central enigma. The obscurely named Black Lodge. Every good series need an enigma. Lost had the island, Death Note had the notebook, Flash Forward, cut down in its prime, had the mass blackout, all gripping concepts with the ability to take the viewer in any direction. With The Black Lodge, even the title is intriguing.

As film-critic and chat show host Jonathan Ross once put it, Twin Peaks is ‘the scariest, weirdest and funniest TV series of all time’, a completely accurate statement. Twin Peaks is a one of a kind drama, a unique and unsurpassable landmark that helped establish television as an artistic rival of cinema. With all of its flamboyant and ambitious scenes, juxtaposing with remarkably restrained subtlety, Twin Peaks is a lurid, luscious and laudable cult classic.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

Exceptional candidate for the best film ever made

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 5 March 2012 11:39

(A review of Citizen Kane )

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 5 March 2012 11:39

(A review of Citizen Kane )The greatest film of all time? In many aspects, yes. Every film watcher knows that there is no definitive greatest film. However, from an objective point of view, Orson Welles’ 1941 masterpiece is a strong candidate. It is literally a perfect film. From its acting, writing and story to its technical composition, Citizen Kane is flawless. Let’s put it in layman’s terms. It’s a fact that it is a good film, it is objectively good. It an opinion not to like it, such a choice is subjective and I respect that. Anyone who tries to claim otherwise is wrong. Citizen Kane is a timeless masterpiece, with an ageless story.

The story is about a man’s emotionally wrought life, all packed into 1 hour and 55 minutes. There are no wasted scenes, there is no time for that. Everything is essential to the story. Nowadays, even a generic thriller or action film takes over 2 hours to tell a story that could easily be told in 90 minutes or less, whereas Welles’ story is a sprawling roller-coaster, kept admirably precise, without appearing short-handed or incomplete in even the slightest sense. How he did it will continue to perplex and astound me.

The plot is magnificent and captivating, exploring the depths of friendship, careers and loneliness. In one of the most well filmed scenes in cinematic history, Kane dies alone in his desolate mansion. Named after the medieval Chinese location of Xanadu, made famous by Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in his poem Kubla Khan, the home is one of the most stark metaphors for the life of the eponymous Charles Foster Kane. As an opening scene, it is memorable and enduring, one that has been lovingly parodied in a number of popular culture staples such as The Simpsons. The home, in its ambitious scope, represents what Kane thought of himself, whilst the unfinished mess of it all arguably portrays his own damaged and lonesome existence. The impressive set design captures the attention of the audience, leading them up to the iconic dying word of Kane. Rosebud. Simple and enigmatic, its meaning is a perpetually fascinating mystery. This minimalist motif manages to segue into one of the most grand and complex investigative stories ever written, escalating into something that is far from minimal. Kane’s final word is an iconic quote, known even to those who haven’t yet seen the film.

Collaborating with Herman J. Mankiewicz, from a family of talented cinematic figures, Welles wrote a story that stands the test of time. Its uniquely personal look at the life of its protagonist, using a non-linear narrative of interviews with surviving associates and flashbacks to various moments from his life, we learn more and more about the elaborate personality of the newspaper magnate. Loosely based on businessman William Randolph Hearst, Charles Foster Kane’s character can be compared to current business figures, such as Rupert Murdoch and several United States politicians. The multi-layered personality, ranging from amiable to alienating, is a richly characterised construct, accentuated by the phenomenal performance by the 26 year old Welles. Playing the role from young upstart to ailing and bitter old man, Welles portrayal is fine representation of his career, a remarkable and unsurpassable tour-de-force.

In a lot of films centred on one primary character, supporting characters are often wasted, relegated to nothing more than background set-pieces. However, despite Welles’ bravura turn, he doesn’t overshadow the rest of the cast or take away from the characters they are playing. He was intelligent enough to know, as both the writer and director, not to steal the spotlight and not to make the film all about one person. This is evidence by the glorious monologues of other characters, such as that of Mr. Bernstein, played with touching sentimentality by the ever under-rated Everett Sloane. In this particular scene, the wistful and sympathetic Bernstein reminisces about a beautiful girl he once saw, wondering what would have happened if he had spoken to her. Such a deep and contemplative scene, entirely told through words, is an example of the huge importance and influence of the other characters on the success of the film. Similarly, Joseph Cotten, another criminally under-rated actor who would later go on to work with Hitchcock (Shadow of a Doubt, 1943) and again with Welles in Carol Reed’s classic The Third Man (1949), delivers a perfect performance as Jedediah Leland, punctuated with typical Cotten charm. One of the most likeable supporting characters of any film, we watch as Leland begins to grow tired of Kane’s ego, worrying about his ambitious friend’s pursuits. Even the minor characters are of huge significance, such as Kane’s mother near the beginning of the film, when we see her about to give away her young son. Delivering a performance of impressive subtlety, Agnes Moorhead’s presence is a commanding one.

Aside from the amazing story, the film is a technical masterpiece too. Orson Welles wanted to create a new level of realism in Hollywood. Before the years of large scale on-location shooting that we have today, Hollywood was primarily limited to studio sets. Welles wanted to eliminate some these limitations. So, with the help of cinematographer Gregg Toland, he went about finding ways to achieve a high sense of realism. One of the most revolutionary ideas was to show ceilings in shots, particularly those filmed from a low angle. Beforehand, this was rarely done because the sets didn’t have ceilings, instead possessing an open top where the cameras and lights would go. To navigate around this, the set designers pulled a piece of material tightly across the open space, to create the illusion of a solid ceiling. In addition to this masterstroke, Welles and Toland experimented with focus. Using deep focus to compose many scenes, a more realistic representation of real life was reached.

His quest for realism is comparable to the Italian neo-realists, who wanted to profile life in post-war Italy in the most realistic ways possible. Whilst films like Vitorrio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves, 1948) favoured mid shots, on-set locations and a style of filming that would now be achieved using hand-held cameras, Citizen Kane reached similar goals by recreating a real life atmosphere through focus and set design. For these reasons, both styles are equally innovative and important to the evolution of cinema.

Under the cinematography umbrella, there is the aspect of lighting that must be touched upon. Employing shadows and on the opposite end of the spectrum, brightly lit scenes to emphasis certain thematic elements, the lighting takes on a life of its own. At some points drawing upon German Expressionist elements, whilst at others relying on a more modernist approach, the film is vividly and beautifully lit, complimenting the plot greatly.

Citizen Kane is a stand out example of how to make a perfect film. An array of characters, tightly constructed scenes of aesthetic quality, convincing make up, cutting edge techniques and a strongly impactful story, it tells a tale like no other. The deep focus that defines the film is a work of genius, made to stand out even more by the rare but necessary uses of shallow focus. Meanwhile, the solid implementation of the camera is a testament to Welles’ mind. Likewise, Bernard Herrmann’s evocative and haunting score is a debut that is every bit as good as his future work. Everything about this film unforgettable.

In regards to the many strengths of the film, it certainly isn’t unfair to claim it is the best film ever made. This is a reasonable accreditation, based on the overwhelming amount of virtuosity found within the stunning classic. Whilst it is impossible to name one film as the best ever, there are few that can top this landmark masterpiece.

The story is about a man’s emotionally wrought life, all packed into 1 hour and 55 minutes. There are no wasted scenes, there is no time for that. Everything is essential to the story. Nowadays, even a generic thriller or action film takes over 2 hours to tell a story that could easily be told in 90 minutes or less, whereas Welles’ story is a sprawling roller-coaster, kept admirably precise, without appearing short-handed or incomplete in even the slightest sense. How he did it will continue to perplex and astound me.

The plot is magnificent and captivating, exploring the depths of friendship, careers and loneliness. In one of the most well filmed scenes in cinematic history, Kane dies alone in his desolate mansion. Named after the medieval Chinese location of Xanadu, made famous by Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in his poem Kubla Khan, the home is one of the most stark metaphors for the life of the eponymous Charles Foster Kane. As an opening scene, it is memorable and enduring, one that has been lovingly parodied in a number of popular culture staples such as The Simpsons. The home, in its ambitious scope, represents what Kane thought of himself, whilst the unfinished mess of it all arguably portrays his own damaged and lonesome existence. The impressive set design captures the attention of the audience, leading them up to the iconic dying word of Kane. Rosebud. Simple and enigmatic, its meaning is a perpetually fascinating mystery. This minimalist motif manages to segue into one of the most grand and complex investigative stories ever written, escalating into something that is far from minimal. Kane’s final word is an iconic quote, known even to those who haven’t yet seen the film.

Collaborating with Herman J. Mankiewicz, from a family of talented cinematic figures, Welles wrote a story that stands the test of time. Its uniquely personal look at the life of its protagonist, using a non-linear narrative of interviews with surviving associates and flashbacks to various moments from his life, we learn more and more about the elaborate personality of the newspaper magnate. Loosely based on businessman William Randolph Hearst, Charles Foster Kane’s character can be compared to current business figures, such as Rupert Murdoch and several United States politicians. The multi-layered personality, ranging from amiable to alienating, is a richly characterised construct, accentuated by the phenomenal performance by the 26 year old Welles. Playing the role from young upstart to ailing and bitter old man, Welles portrayal is fine representation of his career, a remarkable and unsurpassable tour-de-force.

In a lot of films centred on one primary character, supporting characters are often wasted, relegated to nothing more than background set-pieces. However, despite Welles’ bravura turn, he doesn’t overshadow the rest of the cast or take away from the characters they are playing. He was intelligent enough to know, as both the writer and director, not to steal the spotlight and not to make the film all about one person. This is evidence by the glorious monologues of other characters, such as that of Mr. Bernstein, played with touching sentimentality by the ever under-rated Everett Sloane. In this particular scene, the wistful and sympathetic Bernstein reminisces about a beautiful girl he once saw, wondering what would have happened if he had spoken to her. Such a deep and contemplative scene, entirely told through words, is an example of the huge importance and influence of the other characters on the success of the film. Similarly, Joseph Cotten, another criminally under-rated actor who would later go on to work with Hitchcock (Shadow of a Doubt, 1943) and again with Welles in Carol Reed’s classic The Third Man (1949), delivers a perfect performance as Jedediah Leland, punctuated with typical Cotten charm. One of the most likeable supporting characters of any film, we watch as Leland begins to grow tired of Kane’s ego, worrying about his ambitious friend’s pursuits. Even the minor characters are of huge significance, such as Kane’s mother near the beginning of the film, when we see her about to give away her young son. Delivering a performance of impressive subtlety, Agnes Moorhead’s presence is a commanding one.

Aside from the amazing story, the film is a technical masterpiece too. Orson Welles wanted to create a new level of realism in Hollywood. Before the years of large scale on-location shooting that we have today, Hollywood was primarily limited to studio sets. Welles wanted to eliminate some these limitations. So, with the help of cinematographer Gregg Toland, he went about finding ways to achieve a high sense of realism. One of the most revolutionary ideas was to show ceilings in shots, particularly those filmed from a low angle. Beforehand, this was rarely done because the sets didn’t have ceilings, instead possessing an open top where the cameras and lights would go. To navigate around this, the set designers pulled a piece of material tightly across the open space, to create the illusion of a solid ceiling. In addition to this masterstroke, Welles and Toland experimented with focus. Using deep focus to compose many scenes, a more realistic representation of real life was reached.

His quest for realism is comparable to the Italian neo-realists, who wanted to profile life in post-war Italy in the most realistic ways possible. Whilst films like Vitorrio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves, 1948) favoured mid shots, on-set locations and a style of filming that would now be achieved using hand-held cameras, Citizen Kane reached similar goals by recreating a real life atmosphere through focus and set design. For these reasons, both styles are equally innovative and important to the evolution of cinema.

Under the cinematography umbrella, there is the aspect of lighting that must be touched upon. Employing shadows and on the opposite end of the spectrum, brightly lit scenes to emphasis certain thematic elements, the lighting takes on a life of its own. At some points drawing upon German Expressionist elements, whilst at others relying on a more modernist approach, the film is vividly and beautifully lit, complimenting the plot greatly.

Citizen Kane is a stand out example of how to make a perfect film. An array of characters, tightly constructed scenes of aesthetic quality, convincing make up, cutting edge techniques and a strongly impactful story, it tells a tale like no other. The deep focus that defines the film is a work of genius, made to stand out even more by the rare but necessary uses of shallow focus. Meanwhile, the solid implementation of the camera is a testament to Welles’ mind. Likewise, Bernard Herrmann’s evocative and haunting score is a debut that is every bit as good as his future work. Everything about this film unforgettable.

In regards to the many strengths of the film, it certainly isn’t unfair to claim it is the best film ever made. This is a reasonable accreditation, based on the overwhelming amount of virtuosity found within the stunning classic. Whilst it is impossible to name one film as the best ever, there are few that can top this landmark masterpiece.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

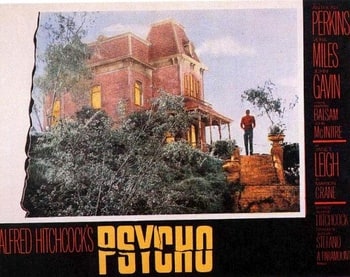

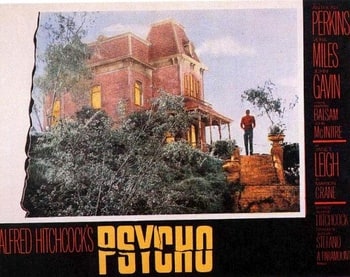

You'd be a psycho not to like this film

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 3 March 2012 05:54

(A review of Psycho)

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 3 March 2012 05:54

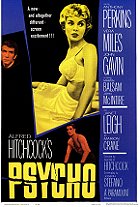

(A review of Psycho)Psycho. Even the name is striking. For a film released in 1960, such a blunt title was daring. How apt, then, that it would be for such a daring film. This was cinema reinvented. This was cinema being borne into a new era. An era that would finally see the end of the Hays code. An era that saw many cultural shifts. An era that saw old Hollywood become new Hollywood. It was a brand new decade and who better to lead the renaissance than Alfred Hitchcock? The master of suspense unleashed his best film. A film better than all the Rear Windows and North by Northwests, or at least more significant. Psycho. A bold title for a bold film. History was about to be made.

There is little to say about Psycho that hasn’t already been said. So I will begin at the start. The opening credits are sharp and searing, created by the legendary Saul Bass. The complex yet minimalist animated sequence, backed by the legendary Bernard Herrmann score, propels the viewer headfirst into a psychologically warped film. The opening score, perhaps not as famous as the shower scene music, is incredibly evocative nonetheless. This is the moment when you know you are watching a good film. It gets uphill from there. Psycho goes from strength to strength, building blocks climbing to the suspenseful peak.

We are introduced to the unconventional leading woman; the first time we see her, she’s wearing nothing more than a bra and a skirt. Yet Marion Crane isn’t simply a subject of what Laura Mulvy would call the Male Gaze. Instead, she is presented as stronger than that. She isn’t being taken care of, rather she is taking care of her financially compromised lover. After stealing some money from her job, a suspenseful trip cumulates as she reaches the Bates motel.

We soon discover, though, that the previous suspense is nothing compared to what else is in store. It’s from here that the film truly develops legs. Marion and as a result, the ever gripped audience, meet Norman Bates, the anxious young motel owner. In perhaps the best male performance of all time, Anthony Perkins truly inhabits his role. Every little tick, every little mannerism, every word of dialogue. It was a performance of such magnitude that he was typecast from here on out. Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins play off each other incredibly well, both appearing anxious, both for obviously different reasons. They tell a story with their body language. Crane, already nervous over her crime, is now feeling uncomfortable about Bates and his unnerving swings from polite to irritable and his troubling commitment to his mother.

Then comes the shower scene. It wouldn’t be foolish to claim this as the most famous sequence in film history. The protagonist is viciously killed by a shadowy figure in a minute long scene that left and still leaves many people too scared to take a shower. Such an unconventional turn of events was truly a daring move. Perhaps this was some sort of divine retribution, punishing her for her crimes. Murdered at her most vulnerable point. Something all men and women fear. Some may claim that this is a step back from the previously independent woman first presented to us at the start. However, what happens here is nothing different to the gangsters shot down in the Warner Brothers films of the thirties. Only this occurs mid way through the film. This was new territory. The fabulously constructed voyeuristic sequence is in itself a mini-masterpiece that has stood the test of time. Few can deny that the scene is still effective. The ingenious use of editing to create a violent slap in the face to viewers, along with the screeching violins, is a perfect example of why Hitchcock was such an indispensable figure in the film industry. His vision helped beckon a new age of film with one single scene. Something he can never be thanked enough for.

Hitchcock’s direction after the infamous scene continues to amaze, with long stretches of silence, only digetic sound present, accentuated by lucid tracking shots. We find our views and beliefs of characters shift about, uncertain of who to root for. With the protagonist gone, what now? Hitchcock cleverly manipulates our feelings through these extended scenes of quietness, the attention now shifted to the enigmatic Norman. Such understanding of the audience is something that Hitchcock excelled at. In fact, he was probably the best of all directors.

Eventually, we are lead to a strong climax, after many mysteries are explored and many twists are turned. The final twenty minutes is one big chilling finale, so taut and well wrapped that it’s almost claustrophobic. The performances are pitch perfect and even if they weren’t, no one would notice, since Perkins would draw us away from any faults. He shines. He is the epitome of a flawless characterisation. Something that many ignorant award ceremonies seemed to ignore. If there is a reason not to trust the Oscars, this probably tops the list.

The film is an example of true craftsmanship. The screenplay by Joseph Stefano, based on the novel by Robert Bloch, itself inspired by the true life crimes of Ed Gein, is full to the brim with intense and infinitely quotable dialogue. The psychoanalytical plot points are of hugely admirable audacity, with Freudian themes present from start to finish. It was a film way ahead of its time. The editing by George Tomasini, who had collaborated with Hitchcock on many of his other masterpieces such as Vertigo, is one of the primary reasons that this film succeeded, the shower scene enough proof of that. The cinematography, filmed in atmospheric black and white, a stark contrast to the vivid colours of his fifties films, is one of the best in any film. Psycho would have lost some if its effect if it were filmed in the more commercially acceptable colour format. The choice to film in black and white remains one of the wisest of all artistic decisions. Then of course, there is the aforementioned score, which is without a doubt, the most important use of music in any film. Psycho is primarily Hitchcock’s genius, yet it is a film that has its strengths in the many. It truly is a film of incredible collaborative genius.

A film of immeasurable essentiality, Psycho’s influence can be seen on a number of other brilliant films, notably Blue Velvet (1986), Halloween (1978), Funny Games (1997), Chinatown (1974) and Blow Up (1966), amongst a sea of others. Psycho’s legacy is beyond impressive, a sign of a priceless classic.

There is little to say about Psycho that hasn’t already been said. So I will begin at the start. The opening credits are sharp and searing, created by the legendary Saul Bass. The complex yet minimalist animated sequence, backed by the legendary Bernard Herrmann score, propels the viewer headfirst into a psychologically warped film. The opening score, perhaps not as famous as the shower scene music, is incredibly evocative nonetheless. This is the moment when you know you are watching a good film. It gets uphill from there. Psycho goes from strength to strength, building blocks climbing to the suspenseful peak.

We are introduced to the unconventional leading woman; the first time we see her, she’s wearing nothing more than a bra and a skirt. Yet Marion Crane isn’t simply a subject of what Laura Mulvy would call the Male Gaze. Instead, she is presented as stronger than that. She isn’t being taken care of, rather she is taking care of her financially compromised lover. After stealing some money from her job, a suspenseful trip cumulates as she reaches the Bates motel.

We soon discover, though, that the previous suspense is nothing compared to what else is in store. It’s from here that the film truly develops legs. Marion and as a result, the ever gripped audience, meet Norman Bates, the anxious young motel owner. In perhaps the best male performance of all time, Anthony Perkins truly inhabits his role. Every little tick, every little mannerism, every word of dialogue. It was a performance of such magnitude that he was typecast from here on out. Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins play off each other incredibly well, both appearing anxious, both for obviously different reasons. They tell a story with their body language. Crane, already nervous over her crime, is now feeling uncomfortable about Bates and his unnerving swings from polite to irritable and his troubling commitment to his mother.

Then comes the shower scene. It wouldn’t be foolish to claim this as the most famous sequence in film history. The protagonist is viciously killed by a shadowy figure in a minute long scene that left and still leaves many people too scared to take a shower. Such an unconventional turn of events was truly a daring move. Perhaps this was some sort of divine retribution, punishing her for her crimes. Murdered at her most vulnerable point. Something all men and women fear. Some may claim that this is a step back from the previously independent woman first presented to us at the start. However, what happens here is nothing different to the gangsters shot down in the Warner Brothers films of the thirties. Only this occurs mid way through the film. This was new territory. The fabulously constructed voyeuristic sequence is in itself a mini-masterpiece that has stood the test of time. Few can deny that the scene is still effective. The ingenious use of editing to create a violent slap in the face to viewers, along with the screeching violins, is a perfect example of why Hitchcock was such an indispensable figure in the film industry. His vision helped beckon a new age of film with one single scene. Something he can never be thanked enough for.

Hitchcock’s direction after the infamous scene continues to amaze, with long stretches of silence, only digetic sound present, accentuated by lucid tracking shots. We find our views and beliefs of characters shift about, uncertain of who to root for. With the protagonist gone, what now? Hitchcock cleverly manipulates our feelings through these extended scenes of quietness, the attention now shifted to the enigmatic Norman. Such understanding of the audience is something that Hitchcock excelled at. In fact, he was probably the best of all directors.

Eventually, we are lead to a strong climax, after many mysteries are explored and many twists are turned. The final twenty minutes is one big chilling finale, so taut and well wrapped that it’s almost claustrophobic. The performances are pitch perfect and even if they weren’t, no one would notice, since Perkins would draw us away from any faults. He shines. He is the epitome of a flawless characterisation. Something that many ignorant award ceremonies seemed to ignore. If there is a reason not to trust the Oscars, this probably tops the list.

The film is an example of true craftsmanship. The screenplay by Joseph Stefano, based on the novel by Robert Bloch, itself inspired by the true life crimes of Ed Gein, is full to the brim with intense and infinitely quotable dialogue. The psychoanalytical plot points are of hugely admirable audacity, with Freudian themes present from start to finish. It was a film way ahead of its time. The editing by George Tomasini, who had collaborated with Hitchcock on many of his other masterpieces such as Vertigo, is one of the primary reasons that this film succeeded, the shower scene enough proof of that. The cinematography, filmed in atmospheric black and white, a stark contrast to the vivid colours of his fifties films, is one of the best in any film. Psycho would have lost some if its effect if it were filmed in the more commercially acceptable colour format. The choice to film in black and white remains one of the wisest of all artistic decisions. Then of course, there is the aforementioned score, which is without a doubt, the most important use of music in any film. Psycho is primarily Hitchcock’s genius, yet it is a film that has its strengths in the many. It truly is a film of incredible collaborative genius.

A film of immeasurable essentiality, Psycho’s influence can be seen on a number of other brilliant films, notably Blue Velvet (1986), Halloween (1978), Funny Games (1997), Chinatown (1974) and Blow Up (1966), amongst a sea of others. Psycho’s legacy is beyond impressive, a sign of a priceless classic.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

A shining achievement

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 3 March 2012 11:28

(A review of The Shining)

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 3 March 2012 11:28

(A review of The Shining)Jack Nicholson’s face grinning menacingly through the axe destroyed door, an iconic image from one of the best and most important horror films of all time. Stanley Kubrick’s first and last horror film, The Shining is one of the most revered, quoted and well known films to have graced the art of cinema. As an adaptation, it has been claimed by many that Kubrick managed to put his own spin on the original novel by Stephen King. Many prefer it, others don’t. Either way you look at it, the film version is a vital and hugely significant classic, that paved the way for many mainstream horror films of the eighties, none of which could top it. The closest a film came to reaching its heights was the shocking and marvellous gore-fest that was The Evil Dead (1981), another one of my favourites.

The plot itself is simple. A man becomes the care-taker of a hotel during its winter season, bringing along his wife and young son. Whilst there, he sinks into madness, putting his family at danger. However, it’s the intricacies within the plot that makes this film more complex. For his seemingly unassuming son has a strange supernatural power, a power that gives the film its title. He is able to see more about the unsettling history of the hotel than anyone else, which allows the audience a gateway into the true terror that awaits.

The film manages to be truly scary and is up there with The Haunting (1963) as one of the most terrifying films of all time. Partly due to the physical points of the story and partly due to the non-digetic aspects of the film, it becomes a deeply unnerving experience. Combine horrific motifs such as the bloody elevators and twins in the corridor with the ear piercing score and isolating steady-cam tracking shots, we have a cocktail of atmospheric terror. The film comes to life through its macabre presentation. The rich photography and art direction gives the film a heightened sense of realism, being that the hotel feels incredibly real, in particular the scenes in which Jack is working on his type writer, light spilling in across the polished floor. The revolutionary and pioneering use of the steady-cam helps give the film a dream-like quality, or rather a nightmarish one. It is one of Kubrick’s best looking films, second only to the visual awe that is 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

The aesthetic qualities compliment and contribute to the scenes of outright horror, including the lady in the bathtub sequence, the ambiguously surreal bear-suit bj scene and the bloodied and mutilated twins in the corridor, which employs a use of sudden edits that truly heighten the fear and surprise of the scene. Meanwhile, the scenes of masterful suspense, such as the baseball bat sequence and most famously, the ‘Here’s Johnny’ scene, are filmed in a way that pushes the imposing sense of dread to the limits.

In terms of performances, Jack Nicholson steals the show. One of the finest portrayals of a maniac is cinema history, he is notable precursor to the flamboyant and eccentric characters such as Christian Bale in the adaptation of American Psycho (2000) and Heath Ledger’s Joker in The Dark Knight (2008), in addition to his own portrayal as the famous Batman villain in 1989.

Opposite him is Shelley Duvall, who is real crowd-splitter when it comes to her performance as Jack Torrance’s burdened yet tolerating wife Wendy. Many say she over-acts, many say she just can’t act at all, whilst others defend her performance. The latter seems to the most unpopular category, which I just happen to fall in. Whilst her performance isn’t amongst the greatest of all time, I think it does her character justice. She is meant to be, to an extent, annoying. She is meant to appear somewhat reverie. She comes across as a naive and weak. After all, aren’t we meant to feel that she is in danger? Her performance allows the viewer to have that allusion, to feel fear for her. Through this irritating quality, she becomes somewhat endearing, since she doesn’t feel all that deserving of the situation she is put in. As the ending of the film draws closer, we see how strong her character can be and the meekness that preceded it sets this up to be all the more heroic. I truly think Duvall doesn't get enough credit for her range, here.

As her son is Danny Lloyd, who delivers one of the finest child performances of all time. He fits the cutesy kid type, like that of Justin Henry in Kramer vs. Kramer from the preceding year, whilst managing to refrain from appearing too clichéd cute. He competently portrays the role without over-doing it and gives a commendably in-depth performance of a strange young boy. I feel that if this film had been made a decade or two earlier, Bill Mumy would have suited the role well, if his performances in Twilight Zone episodes such as It’s a Good Life and Long Distance Call are anything to go by. In addition to the primary cast, a well chosen collection of supporting actors gives the film further credibility, including the magnificent performance from Scatman Crothers.

The Shining is an unsurpassable masterpiece, with far more to it than its most famous scenes. A surreal, nightmarish feature that deserves all the acclaim it gets.

The plot itself is simple. A man becomes the care-taker of a hotel during its winter season, bringing along his wife and young son. Whilst there, he sinks into madness, putting his family at danger. However, it’s the intricacies within the plot that makes this film more complex. For his seemingly unassuming son has a strange supernatural power, a power that gives the film its title. He is able to see more about the unsettling history of the hotel than anyone else, which allows the audience a gateway into the true terror that awaits.

The film manages to be truly scary and is up there with The Haunting (1963) as one of the most terrifying films of all time. Partly due to the physical points of the story and partly due to the non-digetic aspects of the film, it becomes a deeply unnerving experience. Combine horrific motifs such as the bloody elevators and twins in the corridor with the ear piercing score and isolating steady-cam tracking shots, we have a cocktail of atmospheric terror. The film comes to life through its macabre presentation. The rich photography and art direction gives the film a heightened sense of realism, being that the hotel feels incredibly real, in particular the scenes in which Jack is working on his type writer, light spilling in across the polished floor. The revolutionary and pioneering use of the steady-cam helps give the film a dream-like quality, or rather a nightmarish one. It is one of Kubrick’s best looking films, second only to the visual awe that is 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

The aesthetic qualities compliment and contribute to the scenes of outright horror, including the lady in the bathtub sequence, the ambiguously surreal bear-suit bj scene and the bloodied and mutilated twins in the corridor, which employs a use of sudden edits that truly heighten the fear and surprise of the scene. Meanwhile, the scenes of masterful suspense, such as the baseball bat sequence and most famously, the ‘Here’s Johnny’ scene, are filmed in a way that pushes the imposing sense of dread to the limits.

In terms of performances, Jack Nicholson steals the show. One of the finest portrayals of a maniac is cinema history, he is notable precursor to the flamboyant and eccentric characters such as Christian Bale in the adaptation of American Psycho (2000) and Heath Ledger’s Joker in The Dark Knight (2008), in addition to his own portrayal as the famous Batman villain in 1989.

Opposite him is Shelley Duvall, who is real crowd-splitter when it comes to her performance as Jack Torrance’s burdened yet tolerating wife Wendy. Many say she over-acts, many say she just can’t act at all, whilst others defend her performance. The latter seems to the most unpopular category, which I just happen to fall in. Whilst her performance isn’t amongst the greatest of all time, I think it does her character justice. She is meant to be, to an extent, annoying. She is meant to appear somewhat reverie. She comes across as a naive and weak. After all, aren’t we meant to feel that she is in danger? Her performance allows the viewer to have that allusion, to feel fear for her. Through this irritating quality, she becomes somewhat endearing, since she doesn’t feel all that deserving of the situation she is put in. As the ending of the film draws closer, we see how strong her character can be and the meekness that preceded it sets this up to be all the more heroic. I truly think Duvall doesn't get enough credit for her range, here.

As her son is Danny Lloyd, who delivers one of the finest child performances of all time. He fits the cutesy kid type, like that of Justin Henry in Kramer vs. Kramer from the preceding year, whilst managing to refrain from appearing too clichéd cute. He competently portrays the role without over-doing it and gives a commendably in-depth performance of a strange young boy. I feel that if this film had been made a decade or two earlier, Bill Mumy would have suited the role well, if his performances in Twilight Zone episodes such as It’s a Good Life and Long Distance Call are anything to go by. In addition to the primary cast, a well chosen collection of supporting actors gives the film further credibility, including the magnificent performance from Scatman Crothers.

The Shining is an unsurpassable masterpiece, with far more to it than its most famous scenes. A surreal, nightmarish feature that deserves all the acclaim it gets.

0 comments, Reply to this entry

0 comments, Reply to this entry

An enigmatic ensemble classic

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 3 March 2012 09:25

(A review of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?)

Posted : 13 years, 12 months ago on 3 March 2012 09:25

(A review of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?)A descent into madness, watching this film is like having your head compressed in vice. As an audience member, we are invited into the twisted life on an older married couple, whose life is shrouded in a strange ambiguity. Based on the play by Edward Albee, we are turned into voyeuristic spectators, enthralled by the hostility of George and Martha, played with magnificent chemistry by real life husband and wife Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. It is through the eyes of the younger couple, played by George Segal (later famed for his role in the under-rated sitcom Just Shoot Me) and Sandy Dennis that we learn of the troubled marriage, fuelled by bitter rows and personal attacks, often conveyed through a thin veil of comedic jest. As the film progresses, we are drawn deeper into the dark and cynical world of the older couple, much like their unsuspecting guests, who perhaps learn more about themselves throughout the evening than they would have cared for.

This film has a wonderful rhythm, with a fantastically progressive plot. Not many motion pictures can captivate its audience based on few locations and a dialogue heavy script, yet this film succeeds, despite its often dense themes. It’s a troubling experience and one you must commit to, or else you will find yourself unable to fully move with the flow of the film. As the film continues, we are dragged into an increasingly surreal plotline, making this one of the most surreal non-fantasy related films of all time. There are no particular unrealistic moments, setting it apart from the surrealism explored by the likes of David Lynch and Luis Buñuel. Instead, it draws upon the strangeness you find in everyday life to turn this into a tense exploration into the lives of these characters. Speaking from personal experience, I once went into work to find everything had been put into a surreal blender and whilst, of course, there was nothing metaphysically strange, it certainly felt off-kilter. This is much like the film, all of which is within the realms of the real world, only it feels uncanny.

The acting, as you would expect with two Hollywood royals in the mix, is superb. Not a bad performance in the film. Burton and Taylor were born for their roles, each delivering painfully emotional performances. Burton is the extravagant and provoking husband, similar in ways to the popular television character Gregory House (House M.D), only far more perturbing. Taylor is the unbalanced and bitchy wife, who takes no shame in humiliating her husband. Opposite them are Segal and Dennis, each delivering worthy performances. Segal is restrained, each line spoken with a subtle emotion. This juxtaposes with Dennis, who is perfectly acute, delivering a hyperbolic performance that, in any other film, would come across as over-acting, whereas here it is entirely necessary. As far as ensembles go, this is right up there with 12 Angry Men (1957), Magnolia (1999) and Pulp Fiction (1994).

The directing is sublime. Mike Nichols, who would later find huge success with his better known masterpiece The Graduate (1967), doesn’t ever over-play a scene with too many unnecessary close-ups or quick shot successions, instead favouring a more steady directorial style similar to that of Kubrick and Lang. The camera will pan, track and remain static only ever being obtrusive when needed. His style isn’t as abrasive as the more mainstream films of the time, preferring to compliment the themes of the film, rather than over power them.